Clinical history:

67 year-old male with 12-year history of renal insufficiency, on hemodialysis for the past year. Denies a family history of renal disease.The most likely diagnosis is:

- Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

- Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.

- Acquired cystic kidney disease.

- Multilocular cystic nephroma.

- Nephronophthisis.

Risk factors for this condition include (more than one answer may be correct):

- Smoking.

- Male sex.

- Hypertension.

- Duration of therapy.

- Age.

Complications of this condition include (more than one answer may be correct):

- Cyst hemorrhage.

- Renal cell carcinoma.

- Transitional cell carcinoma.

- Berry Aneurysm rupture.

- Cyst infection.

The most likely explanation for the complex upper pole cyst in this case is:

- Renal cell carcinoma.

- Hemorrhagic cyst.

- Oncocytoma.

- Abscess.

The most appropriate management regarding the complex upper pole cyst is:

- Nephrectomy.

- Contrast-enhanced CT for further characterization.

- Follow-up ultrasound in 1 year.

- No further follow-up required.

Discussion:

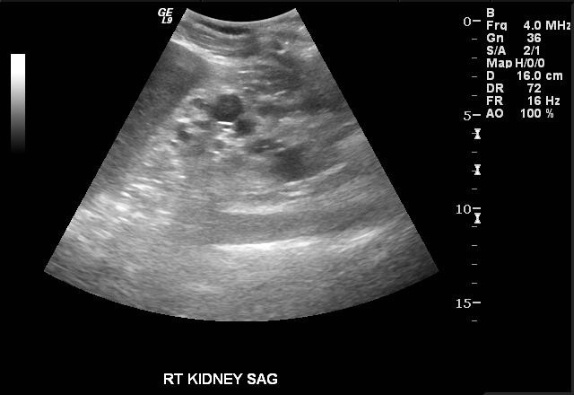

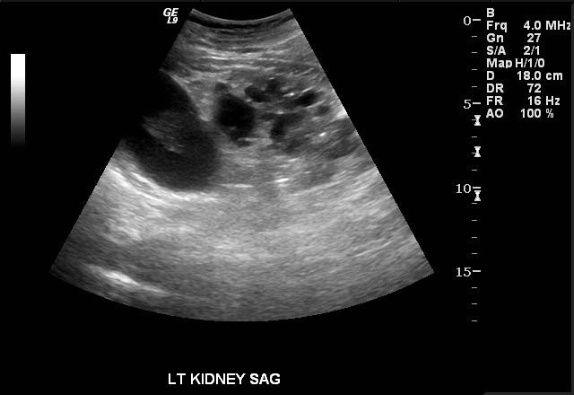

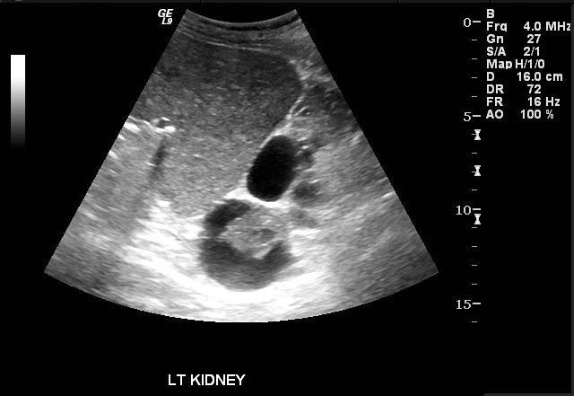

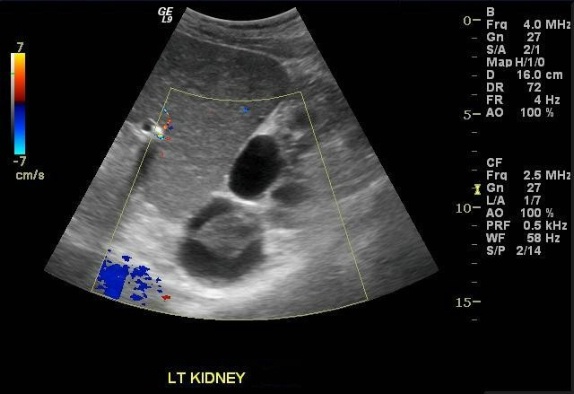

Images demonstrate an echogenic left kidney almost entirely replaced by innumerable cysts of varying size. A dominant cyst at the upper pole contains a complex component. Color Doppler interrogation reveals no vascularity in the complex cyst.

The findings are consistent with acquired cystic kidney disease (ACKD). Up to 10% of cases are unrecognizable by ultrasound due to the small character of the cysts in these instances. When apparent, the cysts vary in size and usually occur in the setting of small, echogenic kidneys.

Described first in 1977 by Dunnill and colleagues, ACKD has gained increasing clinical importance as the life expectancy of patients on renal dialysis has continued to increase. It is defined as “4 or more macroscopic cysts in each kidney of a patient without hereditary cystic disease”1. Dunnill observed a prevalence of 47% in his original autopsy series of 30 dialysis patients. Prevalence increases with the duration of dialysis. ACKD affects up to 90% of patients on dialysis for more than 5 years, irrespective of the type of dialysis received.

The pathogenesis is poorly understood, but one of the most frequently posited explanations attributes cyst formation to the stimulation of tubular epithelium by an undescribed renotropic agent that dialysis fails to clear from the circulation. Immunohistochemical studies confirm proximal tubular epithelium as the principal structural component of the cysts. Most investigators agree that cyst formation is associated with chronic exposure to the uremic milieu. Several authors have documented the development of ACKD in chronic renal failure patients who have not yet undergone dialysis. This phenomenon is supported by the observation that ACKD may have actually been first described a little more than 100 years ago, before the advent of renal dialysis. Male gender, age, African American race, and duration of dialysis are considered the principal risk factors. Regression of disease has been documented following renal transplantation. The role of cyclosporine therapy in the development/persistence of ACKD in renal transplant patients remains under investigation.2,3

The most clinically significant complications are hemorrhage and an increased risk of renal cell carcinoma. Cyst infection is a less common complication. Hemorrhagic cysts are seen in up to 50% of patients with ACKD. Potentially life-threatening retroperitoneal hemorrhage may result if a cyst goes on to rupture. Estimates of RCC prevalence in ACKD range from 7-20%. RCC associated with ACKD is believed to exhibit less aggressive behavior than other types. Since both RCC and hemorrhage may manifest as a complex cyst on ultrasound, further workup is warranted. Contrast-enhanced cross sectional imaging is able to discriminate between these entities on the basis of enhancing components, which will be seen in RCC but not in a hemorrhagic cyst. Alternatively, follow-up ultrasound in 2-3 months should show clearing of a hemorrhagic cyst.

References:

- Moore AE, Kujubu DA. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to acquired cystic kidney disease. Hemodialysis International. 2007; 11:S38-S40.

- Heinz-Peer G, Schoder M, Rand T, Mayer G, and Mostbeck GH. Prevalence of acquired cystic kidney disease and tumors in native kidneys of renal transplant recipients: a prospective US study. Radiology. 1995; 195: 667-671.

- Choyke, PL. Acquired cystic kidney disease. Eur Radiol; 10:1716-1721.

- Scandling, JD. Acquired cystic kidney disease and renal cell cancer after transplantation: time to rethink screening? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007; 2:621-622.

- de Oliveira Costa MZ, Bacchi CE, Franco M. Histogenesis of the acquired cystic kidney disease: an immunohistochemical study. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006; 14:348-352.

- Allan PL. Ultrasonography of the native kidney in dialysis and transplant patients. J Clin Ultrasound. 1992; 20:557-567.

- Lippert, MC. Renal cystic dsease. In: Gillenwater et al, ed. Adult & Pediatric Urology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

- Levine E, Slusher SL, Grantham JJ, and Wetzel LH. Natural history of acquired renal cystic disease in dialysis patients: a prospective longitudinal CT study. Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 156:501-506